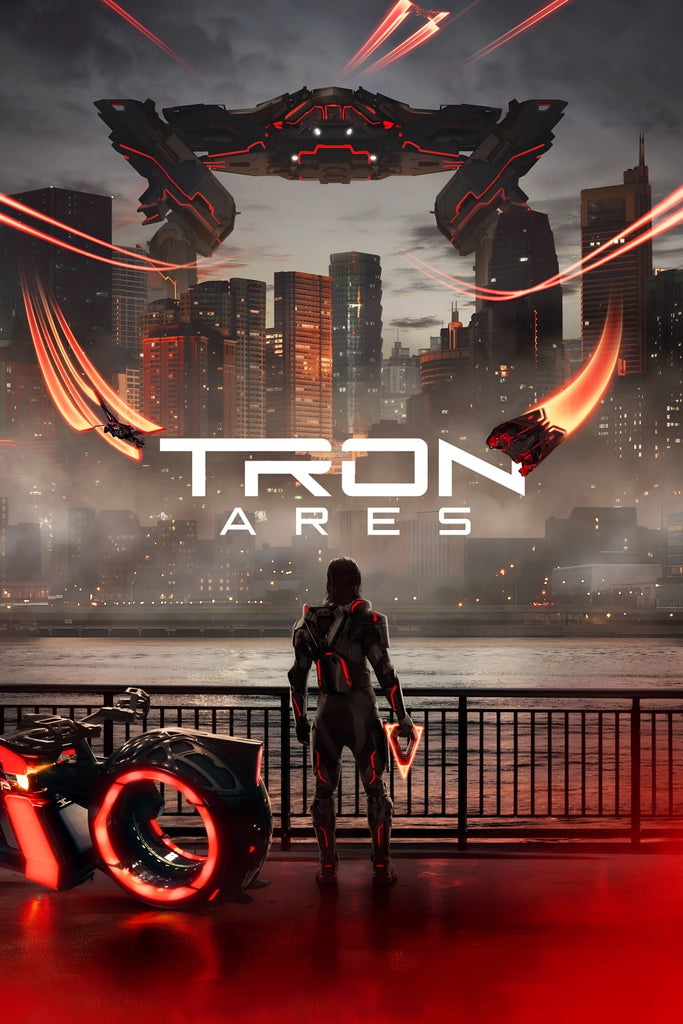

Disney’s TRON: Ares arrives in cinemas with the faint hum of nostalgia and the glow of a dying lightcycle. It’s the latest attempt to reboot the once-radical digital universe born from 1982’s cult classic and reignited (if unevenly) in 2010’s TRON: Legacy. But make no mistake—this isn’t your father’s Grid. In fact, it’s hardly anyone’s Grid anymore. All the original characters have been conveniently “deprecated” from continuity, written out with such neatness it feels less like creative intent and more like an HR memo. Flynn, Quorra, Sam, even the enigmatic CLU—gone. Derezzed from existence so completely you half expect the film to flash a “file deleted” warning.

In their place we have a new generation of neon warriors and corporate schemers, portrayed by a cast whose collective range seems limited to two expressions: intense frown and digital awe. Jared Leto’s Ares, the titular program turned messiah, oscillates between brooding silence and overwrought monologue, while his human counterparts behave like they’re reading the script off a glowing wristband. Emotion feels simulated—ironically apt for a film set in a world of artificial beings, but not quite what the audience signed up for.

Plot-wise, Ares feels like a patch update missing several files. We’re told the Grid now runs on a “Permanence Code,” a supposedly world-changing innovation that somehow just exists, no origin given. How it was developed—or why anyone would trust Dillinger Corp. again, given its cyber-criminal history—is left to the imagination. The company is now run by Edward Dillinger Jr.’s son, the third generation of the same morally grey family somehow still steering the digital empire. It’s an oddly circular inheritance—apparently the Dillinger line survives every reboot unscathed, corporate villainy coded directly into the DNA.

Then there’s the infamous “29-minute time limit”—a supposed countdown central to the story’s tension. Why 29 minutes? Why not 30? The film treats this arbitrary number like sacred code, but never explains its significance beyond “it looks dramatic on-screen.” And for a series that once prided itself on at least pretending to understand the digital frontier, that’s a glaring glitch.

The inconsistencies don’t stop there. We’re told the laser system that digitizes users—originally an experimental marvel in the 1980s—has now evolved into something that can write, store, and transfer DNA. Who invented this laser-writing technology? Don’t ask, because the movie won’t tell you. And when we see the return of Flynn’s original server, somehow existing both in an office tower and in the ruins of an old arcade, the continuity circuits truly begin to fry. The film’s spatial logic reaches peak absurdity when a colossal transport ship emerges from what appears to be a small warehouse—perhaps the most impressive compression algorithm ever conceived.

And yet—despite all this pixelated nonsense—TRON: Ares remains oddly entertaining. Taken on its own terms, detached from the legacy it unceremoniously derezzes, it’s a visually stunning, propulsive sci-fi adventure. The digital cityscapes still pulse with hypnotic beauty; Daft Punk’s absence is keenly felt, but the score tries valiantly to echo their synth-spun energy. The lightcycle chases are kinetic, the fight choreography slick, and the film’s final act—though narratively bonkers—delivers enough spectacle to remind you why the TRON mythos endures.

Perhaps TRON: Ares works best when treated like a rogue program—unstable, erratic, but fascinating to watch until it crashes. It’s not the sequel fans were waiting for, nor the reboot the franchise necessarily deserved, but as a standalone slice of neon escapism, it’s still a fun, glowing ride through the digital afterlife of imagination.