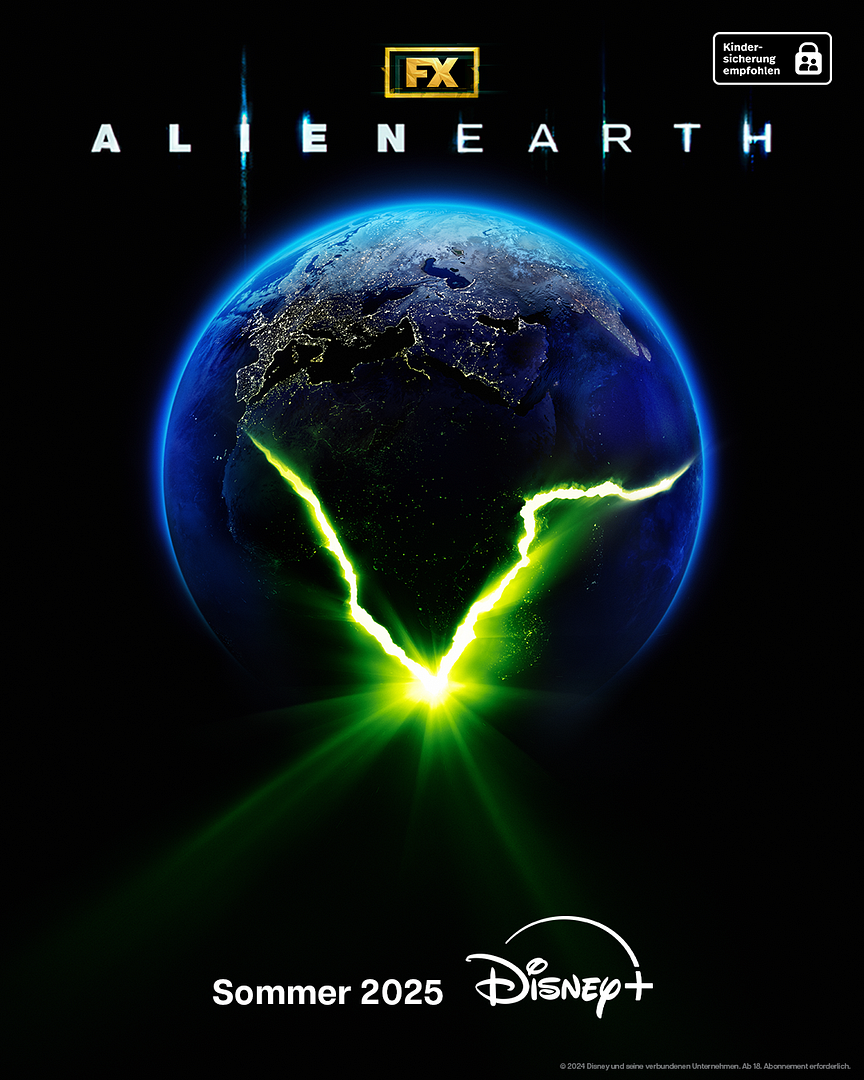

Two years before Ellen Ripley wakes up on the Nostromo, Earth is already broken. Governments have collapsed into five mega-corps, the skies are crowded with falling starships, and humanity’s latest bet on immortality looks disturbingly like childhood stolen and repackaged. Noah Hawley’s Alien: Earth (FX/Disney+) plants the franchise where its title always threatened to go, and—crucially—does it without surrendering the clammy, industrial dread that made Alien mythic. It’s muscular, idea-driven, and (so far) very good.

Where it sits in the canon (and why that matters)

The series is set in 2120, a tidy two years before the events of Ridley Scott’s 1979 film. Think of it less as a side-quest and more as a pressure build: we’re watching the institutions (and appetites) that will later weaponize the Xenomorph learn exactly what they’re dealing with. That framing also lets Hawley nod toward Alien and Aliens while swerving the Prometheus/Covenant cosmology.

The inciting incident: the USCSS Maginot—a Weyland-Yutani deep-space research vessel—crash-lands on Earth, specifically into a gleaming corporate city controlled by a rival conglomerate. Inside the wreck: specimens that should never have reached atmosphere. Outside: security teams, bystanders, and a cross-current of corporate fixers who see profit where we see extinction.

The Five that run the world

Hawley’s Earth is carved up by five corporations—an elegantly nasty backdrop that finally literalizes the franchise’s “company town” subtext:

- Weyland-Yutani (the Americas): the familiar colonizer-extractor behemoth from the films.

- Prodigy (most of Asia, half of Africa, Australia/Greenland): the upstart whose moon-shot is consciousness transfer into synthetic bodies—“hybrids.”

- Threshold (Western Europe), Lynch (Russia), and Dynamic (the Middle East, the other half of Africa—and, by a tossed-off line, the Moon).

The show hasn’t fully detailed the latter three, but it frames Weyland-Yutani vs. Prodigy as the season’s central cold war: bio-weapons and immortality tech as competing endgames.

The emotional core: Wendy & Hermit

At heart, Alien: Earth is about a sister and brother separated by a terrible “miracle.” Terminally ill Marcy becomes Wendy—the franchise’s first human consciousness ported into an adult synthetic body—courtesy of Prodigy’s ethically chloroformed R&D. Her brother Hermit (Joe), now a Prodigy medic/tactical, doesn’t know what she’s become… until the crash brings them into the same blast radius.

Wendy’s presence gives the series its freshest angle: a child’s moral sense trapped in an engineered adult chassis, navigating corporate agendas, a cynical mentor, and appetites (human and not) that view her as asset, savior, or weapon.

Episodes 1–3: the shape of the nightmare

- 1) “Neverland.” A prologue on the Maginot echoes Scott’s original—low light, hum of machinery, bodies waking to a problem you can’t quite name—before the ship augers into Prodigy City in New Siam. Parallel to that, on Prodigy’s island lab (“Neverland,” naturally), Marcy undergoes the procedure that births Wendy. It’s a clean thesis: body horror as corporate deliverable.

- 2) “Mr. October.” The crash site becomes a slaughterhouse, culminating in a haute-decadent gala massacre that’s both bravura set-piece and withering class satire. A tight, unnerving beat: the Xenomorph spares cyborg Morrow, implying a preference for human prey (or a new wrinkle in its heuristics). Meanwhile, Boy Kavalier—Prodigy’s boy-genius trillionaire—sparks a pissing match with Weyland-Yutani over salvage rights.

- 3) “Metamorphosis.” The show widens: dissension among the Lost Boys (Wendy’s fellow hybrids), hints of sabotage, and the arrival of a grotesque “eye” parasite that puppeteers hosts by occupying their socket (a small-scale terror with the series’ creepiest imagery to date). Critics praised the episode’s pivot—still Alien, but mutating into its own thing.

Across these hours Hawley litters Peter Pan breadcrumbs—Neverland, Lost Boys, Wendy, even a would-be Tinker Bell in fan theory form—without losing the franchise’s blue-collar grime. It’s arch, but it scans.

Cast: what they bring

- Sydney Chandler (Wendy) — The Pistol and Sugar alum nails the tightrope between steel and nine-year-old wonder. Her Wendy isn’t Pinocchio; she’s a grieving kid negotiating consent over her own body. Chandler’s profile pieces emphasize just how much of the show sits on her shoulders; she carries it.

- Alex Lawther (Hermit/Joe) — Black Mirror’s “Shut Up and Dance” and The End of the F**ing World* prepped Lawther for twitchy, wounded empathy. As a medic forced to triage the inhuman and the inhumane, he’s terrific—fragile without being flimsy.

- Timothy Olyphant (Kirsh) — A platinum-blond synth with a teacher’s cadence and a knife-edge smile. Olyphant leans into ambiguity—obedient machine or quiet heretic?—and plays the “company android” archetype with lived-in swagger.

- Essie Davis (Dame Sylvia) — The Babadook star threads maternal warmth with corporate calculus as Prodigy’s scientist-custodian of the hybrids. She’s the rare “company person” who feels like a person first.

- Babou Ceesay (Morrow) — A patchwork cyborg in thrall to Weyland-Yutani, channeling a man terrified of obsolescence. The performance has bite; the character has secrets

- Samuel Blenkin (Boy Kavalier) — A peacock-plumed wunderkind CEO whose island is literally called Neverland. Blenkin’s theater pedigree gives Boy an unnerving mix of whimsy and menace. W

How it’s landing (so far)

Early response is strong: Disney reports 9.2 million global views in six days; critics are largely positive on the ambition, production design, and creature work, with some reservations about pace. (It’s a TV novel, not a monster-of-the-week.)

Individual-episode write-ups have been encouraging—Vulture gave Ep.2 four stars; The A.V. Club praised Ep.3’s “thrilling pivot.” The fandom discourse is lively, too, especially over the needle-drop end-credits (Hawley ending cliff-hangers with metal—Tool, Black Sabbath, Metallica) and whether that tonal jolt works. I’m into it; your mileage (and subwoofer) may vary.

Big-ticket world-building you can feel

Reports peg the budget north of $250M—a figure FX hasn’t confirmed but that tracks when you look at the scale. You feel it in the New Siam vistas, the Maginot wreck’s tactile interiors, and the menagerie of new bio-horrors. Shooting across Thailand (and elsewhere) gives the show humid, lived-in texture; the cameras (Dana Gonzales and company) keep it analog-grimy rather than glossy CG.

The money is also on the ideas: practical effects where possible, nasty little organism designs (that eye parasite is instantly iconic), and a corporate geopolitics map that’s simple enough to grok and rich enough to fuel seasons.

How Episodes 1–3 set the table (and what they’re really about)

Beyond the thrills, the first trio is blunt about ownership—of bodies, labor, even death. Prodigy’s hybrid program is sold as salvation but looks like a patent on personhood. Weyland-Yutani’s play is familiar: get the specimen, damn the costs. One quietly chilling beat: a bureaucratic kiosk declining Hermit’s scholarship release because his body belongs, contractually, to the company. This is the Alien universe finally admitting that “the company” isn’t a shadow—it’s the entire sky. Esquire

What might be coming

Episode 5 (airing Sept. 2 in the U.S.) is a flashback to the Maginot 17 days before the crash—expect answers on who carried what, and who opened which door. Meanwhile, the Peter Pan motif seems to be shading from clever to consequential: fan theories now argue Wendy may have a bond with a juvenile Xenomorph (a “Tinker Bell”), a development teased in Ep.4 that could shift the entire human/xeno dynamic from pure predator/prey into something more volatile. Whether that becomes weaponization, alliance, or tragedy… we’ll see. No Season 2 greenlight yet, but the board is set. DeciderCinemablend

Verdict (for now)

Alien: Earth is the rare legacy-IP series that knows why it exists. It keeps the franchise’s claustrophobic terror, deepens the labor/capital critique to a planetary scale, and gives us a protagonist who reframes “what is human?” without leaning on franchise nostalgia to do the work. The first three episodes deliver confident world-building and at least two sequences (the gala, the eye thing) that lodge under your skin and stay there.

If Hawley can land the season with the same control he’s shown in the build, this could be the most vital Alien story since the original duology—one that earns its colon in the title.